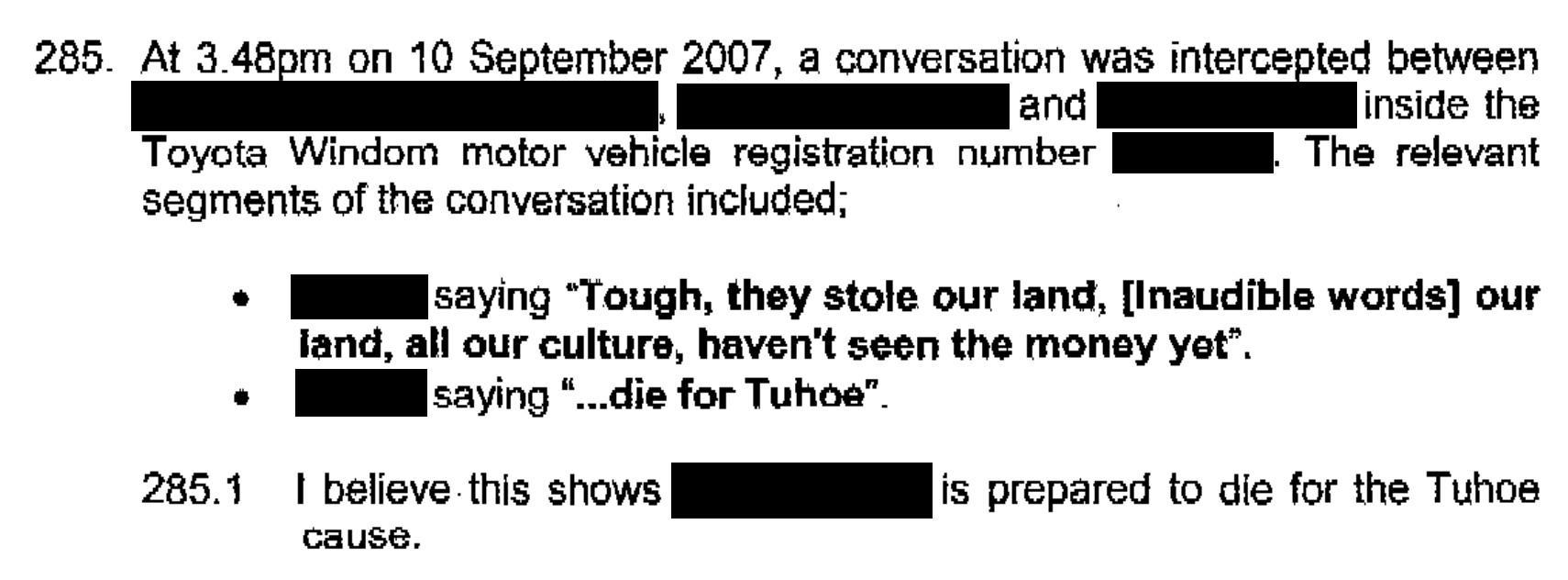

Extract from the court document used to justify the raids, showing how the words “die for Tūhoe,” taken out of context from a private conversation, were used to suggest that someone was “prepared to die for the Tūhoe cause” (personal information censored by the No Trace Project). Tūhoe is a Māori iwi (tribe) whose members were particularly targeted by the operation.

On October 15, 2007, approximately 60 raids targeting Māori indigenous activists, anarchists, and other activists took place across New Zealand as part of an operation called “Operation 8.”[1] A few more raids took place in 2007 and 2008. Around 20 people were arrested and initially accused of participating in a terrorist group and organizing “quasi-military training camps” in remote rural areas. In 2007 the original accusations were dropped and most of the defendants were instead charged with possession of weapons and Molotov cocktails and, for some of them, participation in a criminal group. In 2011 the charges against most of the defendants were dropped and only four people remained charged.[2]

The operation started in 2006 when the police became aware of the “training camps.”[3]

In a 2012 trial:

- Two people were sentenced to 2 years and 6 months in prison.[4]

- Two people were sentenced to 9 months of home detention.[5]

Techniques used

| Name | Description | |

|---|---|---|

| Biased interpretation of evidence | The case was characterized by a lack of evidence that the defendants were planning a specific attack, and relied instead on interpretation of circumstantial evidence.[3] For example:

| |

| Covert surveillance devices | ||

| Audio | Microphones were installed in several vehicles and homes.[3] | |

| Video | Cameras were installed at the “training camps” on several occasions.[3] They were installed shortly before the beginning of the camps and removed shortly after. The goal was to identify who was participating in the camps, what they were doing, and what they were wearing. Footage captured by these cameras showed people:

At least one camera was installed outside a person's home. | |

| Forensics | ||

| Gait recognition | One person was identified in footage of the “training camps” based on their height, gait, and skin color.[6] | |

| House raid | During the raids, investigators seized:[1]

Some of the raids were particularly thorough: cops searched freezers, garbage bins, and compost bins. | |

| Informants | At least two informants were active as part of the operation.[7] In particular:

| |

| Network mapping | Before the raids, investigators spent several months establishing links between people by examining metadata from:[3]

| |

| Open-source intelligence | Investigators obtained information on people from web searches and newspaper articles.[3] | |

| Physical surveillance | ||

| Aerial | On the morning of the October 15 raids, a police helicopter was flying over an area where several raids were taking place, seemingly to surveil the area.[1] | |

| Covert | Investigators regularly followed people on foot and in vehicles.[3] Investigators regularly conducted covert surveillance operations near the “training camps,” but did not get close enough to see what was happening and could only hear shots being fired.[6] | |

| Roadblocks | On the morning of the October 15 raids, police set up a roadblock on the only road leading to an area where several raids were taking place.[1] For most of the day, cops staffing the roadblock searched, questioned, and photographed people passing on the road.[8] | |

| Service provider collaboration | ||

| Mobile network operators | Investigators used the collaboration of mobile network operators to intercept calls and text messages.[3] The intercepted text messages revealed the dates and locations of the “training camps” and who attended them. | |

| Other | Investigators used the collaboration of service providers to obtain information on people from many different sources, including:[3]

Investigators used the collaboration of the New Zealand Army to find out who, in a list of 58 people, had served in the military, presumably to identify who had military experience that they could use to contribute to the “training camps.” | |

Private source.

Now called the Department of Work and Income.

English

English